Liturgy News

Vol 40 No 1 March 2010

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

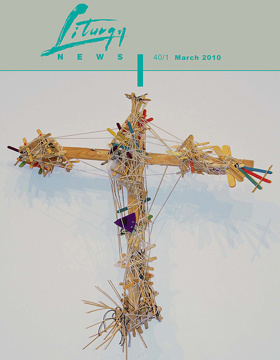

| Our Cover: The Cross | Elich, Tom | Australian Images | 1, 16 |

| Editor: The New Translation: Dread or Delight? | Elich, Tom | Texts – Liturgical | 2 |

| With Special Love: Mary, Mother of God | Foster, Judith | Mary, Mother of God | 3-4 |

| Litany of Mary Help of Christians | Foster, Judith | Australian Composers / Music | 5 |

| Liturgical Music for Feasts of the Virgin Mary | O’Brien, Jenny | Mary, Mother of God | 6-7 |

| Renew Your Church by the Light of the Gospel | O’Regan, Patrick | Texts – Liturgical | 8-9 |

| Chupungco Looks Forward | - | History of Liturgy / Vatican II | 10 |

| NLC Membership | - | People | 10 |

| In Memoriam: Edward Schillebeeckx, Richard Proulx | - | In Memoriam | 10 |

| new canon onthe deacon | - | Ministries – Liturgical | 11 |

| An Image for Good Friday | - | Art | 11 |

| Graeme and Ralph Morton | - | People | 11 |

| Publisher for the Missal | - | Texts – Liturgical | 12 |

| Unity Chapel | - | Liturgy - Other Churches/Religions | 12 |

| New Liturgy Head in Paris | - | People | 12 |

| Lectionary | - | Texts – Liturgical | 13 |

| Canonisation in October | - | Saints | 13 |

| Music Resource Project Hits a Snag | - | Music | 13 |

| Japenese Ghosts | - | Texts – Liturgical | 13 |

| Australia: And a Good Friday Was Had by All (Bruce Dawe) | Kelly, Anthony | Easter and Lent | 14 |

| Books: Keep the Fire Burning (Ken Canedo) | Fitzpatrick, Michael | Music | 15 |

Editorial

Editor: The New Translation: Dread or Delight?

Elich, Tom

Notwithstanding the languishing and musing of the consumptive Romantic poet John Keats, I found the movie Bright Star a profound cinematic experience, one that led me to dig out my old poetry books to rediscover some of his verse. The fourteen lines of the sonnet which gave the movie its title form but a single, difficult sentence. I needed to read it aloud over a dozen times before I began to get it right. Our newly translated collects may not always have the poetic lucidity of John Keats but, like the sonnet in its complexity, may require a dozen attempts aloud before we begin to get it right. How should we approach the new translation of the Missal?

At the outset, I suppose I should declare my hand. In my judgement, the 2001 charter for translation, Liturgiam Authenticam, is a poor document, an embarrassment for the Church. It wrongly presumes that languages correspond literally, verbally and grammatically. It reduces the mandate of bishops conferences who prepare the vernacular liturgical books, restricting them to translating the Latin without any new compositions or pastoral rearrangement of the rites. It wrests overall control of the process from the local bishops conferences in favour of the Holy See. Yet this is the document in possession and there is no indication that its provisions are open to revision or dialogue. This is the document which established the new ICEL (International Commission on English in the Liturgy) which is responsible for the translation we are about to receive.

I also need to say that I was involved in the work of the old ICEL during the 1990s, most notably in the preparation of the Revised Sacramentary. This twenty-year project, approved by all the English-speaking bishops conferences, was summarily rejected by the Holy See. Prepared according to the previous charter for liturgical translation, Comme le prévoit, this work incorporated not only subtle and supple translations from the Latin, but also extensive new material, both pastoral notes and new prayer texts. In the last decade, this rich version of the Missal has been studiously and publically ignored. The forthcoming translation is always compared with the text we have used for almost forty years and never with the text we should have already been using for a decade.

I find myself smiling at the rhetoric of the new ICEL and the bishops involved with its work. Not until this translation project, we hear, did they understand the rich biblical allusions to be found in the liturgical texts, not until now has the nuance and theological depth in the Latin texts been revealed. It is a little like the colonial explorer who presents a personal discovery as a new reality. What they discovered invariably was always there and was appreciated by other people for generations before them. Certainly those involved in the old ICEL well understood the riches of the liturgical texts and, I would suspect, many of those who prayed these texts for a lifetime did as well.

The real issue is how our Missal translation provides eloquent and transparent testimony to the theology of the liturgy, its feasts and celebrations. Forty years ago our scholars sought clear, simple sentences which could be readily understood in the hearing. The rites should be marked by a noble simplicity; they should be short, clear and unencumbered by useless repetitions; they should be within the people’s powers of comprehension and as a rule not require much explanation (SC 34). We have learned over the last half century that people can handle a more extensive vocabulary and a greater level of grammatical complexity, which allow for a fuller expression of our liturgical praying. This is what the Revised Sacramentary attempted to do a decade ago.

The forthcoming translation however takes it much further, using convoluted expressions, incomprehensible words and ungrammatical sentences in its attempt to be faithful to the Latin. Here I am agreeing with American Bishop Donald Trautman who has thus criticised the new translation. At the insistence of Liturgiam Authenticam, these texts seem to be primarily about the Latin; the Second Vatican Council tried to get beyond the Latin by introducing the vernacular and encouraging local expression.

Now however the decade for comment and feedback has expired. Criticism from bishops and liturgical scholars has certainly made some difference as ICEL revised drafts and presented final texts to the Holy See and bishops conferences. Next – if the first part of the Missal to be approved (the Order of Mass) is anything to go by – the Holy See, assisted by the Vox Clara committee, will revise the text at whim, and we will have it to print in our new liturgical books. This is it. It is accomplished. So how should we approach the new translation of the Missal?

I do not think I can pretend before our people that we are getting lucid, poetic prayers. But this is what the Church has produced for our use at this time. I willingly accept that the translators, bishops and administrators who have laboured to produce these texts over the last decade have done so as sincerely, faithfully and generously as we ever did in the old ICEL. Irrespective of any disagreements, we all seek to do the best for the Church and, at this juncture, that means enabling the Church to retain its voice at prayer. We must learn how to use these words for our prayer – to praise, bless and thank God, to ask for God’s help in our need. If we face a Collect and ask ourselves, What on earth does it mean?, we have no option but to study the text and analyse its grammar, to read the text aloud and to repeat it until it begins to gel in our minds and hearts. Whether we like it or not, such hard work will have the benefit of leading us more fully into the beauty of liturgical prayer.