Liturgy News

Vol 41 No 2 June 2011

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

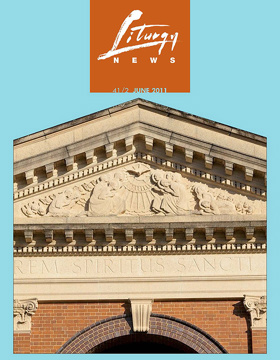

| Our Cover: Daphne Mayo II | Elich, Tom | Australian Artists | 1, 16 |

| Editor: Understandings and Misunderstandings | Elich, Tom | Texts – Liturgical | 2 |

| Altar to Sickbed | O’Rourke, Ursula | Pastoral Care of the Sick | 3-4 |

| The Magical Mystical Deanery Tour | Harrington, Elizabeth | Texts – Liturgical | 5 |

| Silent Worship | Arden, Tony | Liturgy - Other Churches/Religions | 6-7 |

| Can One Liturgy Span Two Locations? | Nettleton, Nathan | Technology | 8-9 |

| Bureligh Heads Parish Banners: Parables of the Kingdom | - | Australian Images | 9 |

| Sant'Anselmo - 50 years old | - | History of Liturgy / Vatican II | 10 |

| Vox Clara | - | Texts – Liturgical | 10 |

| Back to the Future | - | Devotions | 10 |

| St Mary MacKillop - Solemnity | - | Saints | 10 |

| Quotable Quotes on Preaching | - | Liturgy of the Word | 11 |

| Australian Pastoral Musicians Network | - | Music | 11 |

| Larry Madden | - | In Memoriam | 11 |

| Celebrating Old language | - | Word | 11 |

| St Mary's Kinglake | - | Architecture and Environment | 11 |

| New Cathedral - Bunbury | - | Architecture and Environment | 12 |

| New Missal | - | Texts – Liturgical | 12 |

| More on the Tridentine Mass | - | Liturgy | 12 |

| Altar Breads | - | Symbols | 12 |

| Electronic Church Music | - | Music | 12 |

| The PLACE for the Choir and the Musical Instruments | Hackett, Stephen | Music | 13-14 |

| Books: Anscar Chupungco, What then is Liturgy? | Cronin, James | Liturgy | 15 |

Editorial

Editor: Understandings and Misunderstandings

Elich, Tom

We do not have to like the new translation of the Missal. We do not have to agree with the authoritarian process by which it was produced. But we do now need to learn to appreciate it and pray with it so that the words we use will still be a window to the sacred and allow the gathered Church to express its worship of God.

With time, favourite phrases will begin to carve themselves into our minds and hearts. Perhaps one place to start is with the concrete images which have been revealed in the new text: a serene and kindly countenance (EPI); break the bonds of death; sending the Spirit like dewfall (both in EPII); from the rising of the sun to its setting (EPIII).

However, we will regularly have to work harder to avoid misunderstandings. The new translation is touted as uncovering the scriptural references in the text. One clear example of this occurs in the invitation to communion. I doubt that anyone familiar with the story of the centurion’s sick servant would have missed the reference in the translation we have used to date. Nevertheless, the people’s response now quotes the centurion’s words more fully, as the Latin does: Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof... (Mt 8:8, Lk 7:6). The words which invite this response refer to the Lamb of God who takes away our sins. The dialogue recognises our need as sinners for the healing word of Christ, so we confess that we are not worthy to be in the company of Christ. The danger with the phrase enter under my roof is that people will take it at face value and say, ah yes, the roof of my mouth. This is not just a quaint misunderstanding, but enshrines an unhelpful theology limiting and localising the real presence of the living risen Christ in the blessed Sacrament. It is not as though Christ is somehow trapped within the host. As Nathan Mitchell once wrote, the body of Christ is present in the Eucharist not in the usual, natural, visible, local ways bodies are normally present, but rather in a spiritual, nonvisible, substantial, and sacramental manner… (Real Presence: the Work of Eucharist, Chicago: 1998). In scholastic terms, locality belongs to the accidents of the bread and wine, not the substance of Christ’s body. The risen Christ no more enters our mouth than he is prisoner in the tabernacle. Such a misunderstanding reduces the reality of the real presence.

The translation is sometimes less scriptural in its wording, and this too creates problems. I am thinking here of the words of institution over the wine. All modern translations of the biblical narrative use the

word cup. The Latin calix is a general word for a drinking vessel, not in any way limited to the ecclesiastical goblet we call a chalice. It would be wrong to imagine from this usage that Jesus celebrated the ‘first Mass’ at the Last Supper – the paschal mystery of his death and resurrection had not yet been accomplished. How then are we to appreciate such a text in our liturgical prayer? I suggest we need to recognise it as a deliberate variation to scriptural text designed to move the institution narrative away from any historical sense of mere re-enactment; instead the usage affirms that these are our ritual words which Christ speaks in the here and now in our liturgy. The word chalice on the priest’s lips corresponds to the vessel in his hands. Ironically, cup is retained in the second people’s acclamation which follows the institution narrative

when conceivably chalice might have been quite serviceable.

Another change with which I hope will always be a struggle for people is the misleading English translation of pro multis as for many. Although it is literally correct, this English wording flatly contradicts the Catholic faith that Christ died for all (2 Cor 5:14-15 and Catechism of the Catholic Church, 605). Originally in 1970, the translation for all was defended by the Holy See, but then a 2006 circular letter from the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments pointed out that ‘for many’ is a faithful translation of ‘pro multis’ whereas ‘for all’ is rather an explanation of the sort that belongs properly to catechesis. The strangeness of other possible translations such as ‘for the many’ or ‘for the multitude’ might at least have puzzled people towards a good theological understanding. In praying the new translation, we will need to emphasise other phrases which correct any misunderstanding. The third acclamation acknowledges Christ as the Saviour of the world. Eucharistic Prayer III provides a useful counterbalance as it draws the peace and salvation of all the world within the scope of this Sacrifice of our reconciliation. Eucharistic Prayer IV describes the work of Christ as sharing human nature in all things but sin, proclaiming salvation to the poor, prisoners and the sorrowful, and sanctifying creation to the full; it speaks of the sacrifice acceptable to you which brings salvation to the whole world.

A final example of how a nuanced understanding of the new translation is required occurs in the response, And with your spirit. There is no ground for thinking that it recognises some special gift of the Holy Spirit which the priest has received by virtue of his ordination and which therefore is meant to separate the ordained minister from the rest of the people of God. The phrase is used by St Paul to address the entire community: May the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with your spirit, brothers and sisters (Gal 6:18); My greetings to every one of God’s holy people in Christ Jesus... May the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ be with your spirit (Phil 4:21-23; see also 2 Tim 4:22 and Philemon 25). The dialogue between priest and people does seems uneven when we just look at: The Lord be with you. And with your spirit. But it takes on a rather different colour in the context of the longer greetings when the priest says, The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the love of God, and the communion of the Holy Spirit be with you all, or, Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. Here it is clearer that what we intend is a mutual spiritual blessing, by which God’s love and grace constitute the assembly as the Body of Christ. The Lord be with you can be regarded as a kind of abbreviation of these more ample greetings. The people reply with emphasis on the third word rather than the last, And with your spirit, because the greeting is in fact a symmetrical recognition on the part of both priest and people that Christ is present in the gathered Church.

In sum, the new translation provides rich texts for our worship but they are more difficult. It is imperative that we make the effort to understand and use them well.