Liturgy News

Vol 45 No 4 December 2015

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

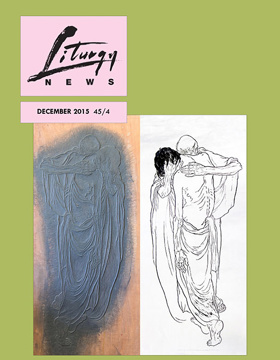

| Our Cover: Frank Wesley - The Forgiving Father | Farrell, Lindsay | Art | 1, 16 |

| Editor: Time for Tough Talking | Elich, Tom | Texts – Liturgical | 2-3 |

| Celebrating God's Mercy in Sacrament, Word and Song | O'Brien, Jenny | Eucharist / Mass | 4-5 |

| Determining the Canonical Weight of a Liturgy Document | Schwantes, Clare | Texts – Liturgical | 6-7 |

| Restoration of Saints Peter & Paul - Bulimba | Elich, Tom | Architecture and Environment | 8-9 |

| Composing, Performing, Listening | Morton, Ralph | Music | 10-11 |

| Hymn Books Ready | - | Music | 12 |

| Randall Lindstrom | - | People | 12 |

| Watch This Space | - | People | 12 |

| Denis Hurley Centre | - | People | 12 |

| Date Claimer - Australian Academy of Liturgy | - | Catechesis - liturgical | 12 |

| Recognition - Sister Susan Daily | - | People | 13 |

| New Rites for Marriage and Confirmation | - | Texts – Liturgical | 13 |

| LabOra Marriage | - | Marriage | 13 |

| Pope Shares Journey | - | Eucharist / Mass | 13 |

| Eastern Rite Catholic Churches | Harrington, Elizabeth | Liturgy - Other Churches/Religions | 14 |

| Books: What We Have Done, What We Have Failed To Do. Assessing the Liturgical Reforms of Vatican II | Cronin, James | History of Liturgy / Vatican II | 15 |

Editorial

TIME FOR TOUGH TALKING

Elich, Tom

The project to provide a new Lectionary for Australia is a mess. It is time for some tough talking and firm decision making.

As a liturgical book, the Lectionary is basically just a list of Scripture references. So unlike most of our liturgical books, the Lectionary has not been translated from Latin into English for use in the liturgy. Rather we have opted to use an existing Scripture translation with some very minor adjustments for the opening words of a reading. In the 1970s, a range of Scripture translations were approved for liturgical use, one of which was selected for the official Lectionary. Australia, the British Isles, Canada and other countries used the Jerusalem translation. In the decades since the 1950s, most Scripture translations were undergoing revision to reflect advances in biblical scholarship and changing usages in the English language.

Twenty-five years ago, with their Lectionary out of print, the Canadian bishops conference decided to prepare a new Lectionary using the NRSV. The volume for Sundays was published in 1992 and the two volumes for weekdays in 1993-1994. At this time the bishops in the USA proposed two editions of the Lectionary, one using a revised NAB and the other using the NRSV. The Australian Catholic Bishops Conference voted in July 1993 to publish its own NRSV Lectionary using the revised Grail psalms and basing it on the Canadian publication. This got to the stage of calling for tenders from publishers so that it would be ready when the expected revised Sacramentary was ready for use later in the decade. Popular resources began to use the NRSV and, since our Lectionary too was out of print, parishes began to order the Canadian Lectionary.

Meanwhile the Holy See was in the process of translating the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1994). It originally used the NRSV throughout but, by decision of Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, most of it was replaced with the older RSV. The Congregation formed the opinion, in agreement with strong right-wing lobbyists, that the NRSV was shaped by a feminist ideology. This was communicated to the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments who moved to stop the use of the NRSV in the liturgy. The December 1994 meeting of the Australian bishops conference resolved to seek to enter into dialogue with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, alone or in conjunction with other episcopal conferences, to identify and resolve any difficulties which the NRSV may present for use in liturgy and catechesis. In practice the negotiations fell to Canada but, because they had just published their books (which they were allowed to continue to use), there was little pressure to find quick solutions. By 2000, the Canadian bishops had received lists of hundreds of changes required by the Holy See. The bishops sought to resolve key six issues with the Holy See (unnecessary changes to the NRSV text, the arbitrary exclusion of the word ‘human’, archaic expressions, use of masculine nouns and pronouns, determining the translation according to factors beyond the biblical text itself) but gained no ground.

At this point, the translation of the revised Sacramentary was rejected by the Holy See, the charter for literal translation Liturgiam Authenticam was promulgated, and the new ICEL – directed entirely by the Holy See – set about producing a new translation of the Roman Missal.

The necessity of having a new Lectionary at the same time as a new Missal however was not lost. This is important for the publication of all the ritual books, people’s missals and other liturgical resources which combine prayer and Scripture texts. So in 2003, with the approval of the Holy See, a number of English speaking countries clubbed together to prepare a new Lectionary using the NRSV. (The USA had long since settled for the NAB and had let the idea of a NRSV Lectionary drop.) Australia, New Zealand, England and Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Malaysia-Singapore, Philippines and South Africa formed the International Commission for the Preparation of an English-language Lectionary (ICPEL) which met for the first time early in 2006. Everyone was very hopeful, because in 2007 the Canadian NRSV Lectionary finally received the approval of Rome’s recognitio. Once again contracts were signed and drafts of a Lectionary based on the Canadian book were circulated. However ICPEL failed.

ICPEL had brokered a delicate deal with the NRSV copyright holders to make changes to the text along the lines of what had been agreed for Canada, but the Holy See then insisted on the right to make whatever changes it wished to the text. A solution mutually acceptable to bishops conferences, the copyright holders and the Holy See could not be found. ICPEL then tried the same approach using the RSV or the ESV translations, but both attempts foundered for the same reason.

In 2010, a letter from the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments blocked the move to allow other countries to adopt the model of the Canadian Lectionary. At the end of 2013, Australia in frustration announced that it was withdrawing from ICPEL and would reprint the existing Lectionary using the Jerusalem translation. At least, they argued, it is in possession, it is well-known, and it has now been used in people’s missals and ritual books with new Missal translations. But it seems this will not be possible either.

In October 2015, ICEL convened a meeting with Archbishop Arthur Roche from the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments to discuss the use of the revised Grail psalms. In the course of this meeting it was made clear that the position of the Congregation is that the NRSV translation is not suitable for liturgical use because it is shaped by a feminist ideology; the compromise reached with the Canadian bishops will not be extended to any other bishops conference; and the RSV or ESV translations are deemed by the Congregation to be acceptable, but not the Jerusalem, because of Liturgiam Authenticam’s demands for a literal translation. The ICEL bishops have come back to their respective conferences proposing a common translation for countries outside North America using the ESV and the 2010 Grail Psalms.

It is time to bring this saga to a sensible solution. Our Lectionary has been out of print for over twenty years and parishes have been ordering one wherever it is available – from Canada or even the United States. There has been great uncertainty with each new publication of a liturgical resource.

It is time for the English-speaking conferences of bishops to do some tough talking in Rome. Archbishop Roche set out the position of the Congregation for Divine Worship. Bishops need to present the argument for following Canada in using the NRSV. It must be possible to reach agreement with well-educated and committed people on both sides. Respectfully and firmly, Canada was able to work it out. The German bishops have been able to deal with the Congregation when they decided to withdraw their new translation of the funeral rites and shelve their new translation of the Missal.

There are many reasons for the English-speaking bishops conferences to pursue an NRSV Lectionary.

* The work is already done for Canada. Why is this considered unsuitable for the rest of the world? It is a proven success after two decades of use. It has always been the aim to have a common translation of the liturgy for all countries where English is used.

* The NRSV is a literal translation, up-to-date in its scholarship and prepared with the participation of Catholic experts. It carries an imprimatur.

* It uses standard, contemporary English. The presumption that a feminist ideology is enshrined in its modest use of inclusive language is unfounded: this is standard English usage in universities and government.

* It is an ecumenical translation, widely used in the liturgy of other churches. A common Scripture translation is recommended by the Ecumenical Directory (1993).

* The NRSV is the only literal English translation of the Bible known and used across the English-speaking world, both in study and prayer.

TOM ELICH

Editor