Liturgy News

Vol 47 No 1 March 2017

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

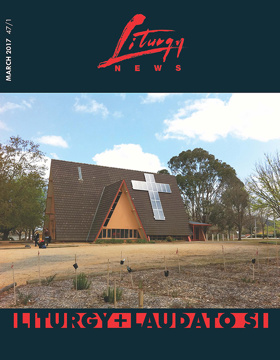

| Our Cover - Liturgy and Laudato Si: The Church Building | Moran, Julie | Architecture and Environment | 1, 16 |

| Editor: Dark Symbols | Elich, Tom | Symbols | 2 |

| Saints and Martyrs | Kirchhoffer, David G | Saints | 3-4 |

| Good Eucharistic Practice 1: Communion from the Altar | - | Eucharist / Mass | 4 |

| Sunday - the Original Feast | Craig, Barry | Sunday | 5-7 |

| Work in Progress | - | Architecture and Environment | 7 |

| Sacraments With People With Disability | - | Sacraments | 7 |

| Congress on Sacred Music | - | Music | 8 |

| Liturgy News Covers 2017 | - | Architecture and Environment | 9 |

| Geothermal Heating | - | Architecture and Environment | 9 |

| Leonard French | - | In Memoriam | 9 |

| Patrick Regan | - | In Memoriam | 9 |

| Cuthbert Johnson | - | In Memoriam | 9 |

| Music Director | - | People | 9 |

| LabOra Marriage | - | Marriage | 9 |

| Liturgical Translations | - | Texts – Liturgical | 10 |

| Bishop in the Crypt | - | Funerals | 10 |

| Family Centred Sacramental Preparation | - | Sacramental Preparation | 11 |

| Liturgical Ministry: Thinking Beyond the Roster | Murrowood, Cathy | Ministries – Liturgical | 12-13 |

| Musical Revolution: An Invitation To Renewal | Robinson, James | Music | 14 |

| Books: At the Heart of the Liturgy. Conversations with Nathan D Mitchell's 'Amen Corners' 1991-2012 | Cronin, James | Liturgy | 15 |

Editorial

DARK SYMBOLS

Elich, Tom

Moby Dick was a huge whale, hunted across the globe by the obsessive Captain Ahab who sought to avenge the loss of his leg to the whale on a previous whaling expedition. His ill-fated quest is the subject of the sprawling mid-19th century novel by Herman Melville. Moby Dick was white.

In Chapter 42, the narrator reflects on the Whiteness of the Whale, on the rather vague nameless horror concerning him, which at times by its intensity completely overpowered all the rest; and yet so mystical and well nigh ineffable was it, that I almost despair of putting it in comprehensible form. It was the whiteness of the whale that above all things appalled me.

There follows a passage extolling the refined beauty of whiteness – in marble sculptures and pearls, the innocence of brides and the benignity of age. White is used in liturgical vesture for solemn celebration and the alb derives its name from the Latin word for white. In the Vision of St John, the redeemed are clothed in white robes and they stand before the great white throne. Yet for all these accumulated associations, with whatever is sweet and honourable and sublime, there yet lurks an elusive something in the innermost idea of this hue, which strikes more of panic to the soul than that redness which affrights in blood. This elusive quality it is which causes the thought of whiteness, when divorced from more kindly associations and coupled with any object terrible in itself, to heighten that terror to the furthest bounds.

This is how symbols work, for symbols are multivalent, even ambivalent. We speak of water as a sign of life and growth, and yet we know that water is for drowning in. That is why our liturgical books recommend baptismal immersion, to reveal the reality of dying and rising with Christ. The security of the womb is wrenched open when the waters break and the newborn is brutally thrust into a new existence.

We express the joy of Easter resurrection with a bonfire and carry the flames into the darkened church. Yet every Australian knows the destructive power of bushfire, a terrible association made raw by our safe electric heat and light. Open fires are a rare experience in urban life and hold an edge of terror.

What then of the dark side of whiteness? It rears its head already in Melville’s catalogue of the beauties of whiteness. This pre-eminence in [whiteness] applies to the human race itself, giving the white man ideal mastership over every dusky tribe. A century and a half later, the issue here is clear, but it is not blunt. It presents itself rather subtly. Whiteness theory treats whiteness as a social construct; it is normalised, taken for granted and is therefore invisible. (The history of whites in Australia is just plain Australian history.)

How then do we articulate a baptismal theology of whiteness? Baptism is an act of ritual cleansing and purification. By this washing, we are admitted to the community of those who are saved by Jesus’ death and resurrection. The anointing with chrism which follows the washing is a welcome into Christ’s holy people and then immediately the newly baptised is clothed in white: You have clothed yourself in Christ; see in this white garment the outward sign of your Christian dignity.

The lectionary for the catechumenate includes the words of Psalm 51:

O wash me more and more from my guilt

and cleanse me from my sin…

O purify me, then I shall be clean;

O wash me, I shall be whiter than snow.

Does the elusive menace of the white whale lurk in our baptismal symbolism of washing and purity? Given the invisible and normative presumption of whiteness in Australia, can we any longer innocently associate baptismal purity with whiteness? Is there an unspoken assumption that the Christian community, washed in baptism and beloved by God, is ‘normally’ white?

St Paul writes strongly to the Church at Galatia:

Every one of you that has been baptised has been clothed in Christ. There can be neither Jew nor Greek, there can be neither slave nor free, there can be neither male nor female – for you are all one in Christ Jesus (3:27-28; see also Col 3:11).

As a person descends into the font to be washed clean, is not whiteness the dirt to be washed away? As a person descends into the font to die to the old self and put on Christ, is it not the taken-for-granted privilege of whiteness which must die? What do we mean when we say that the white garment is the outward sign of our Christian dignity when baptism means the setting aside of whiteness rather than the embrace of whiteness?

It is ultimately a question of how those baptised into Christ exist without compromise in an imperfect world. Baptism ought mark a certain disjunction with the society in which we live, an affirmation not of the status quo but of a solidarity with the oppressed and disadvantaged. How does the Christian become a sign of the kingdom of God?

+++

These reflections have been prompted by a very challenging article in Worship (July 2016) by Andrew Wymer and Chris Baker: “Drowning in Dirty Water: A Baptismal Theology of Whiteness”. Against the background of several black deaths in custody, the authors put some very challenging questions. One sentence from their conclusion reads: White people who have not examined how we have been complicit and benefitted from the oppressive forces of whiteness, white privilege and white supremacy enter the Red Sea of baptism primarily as the oppressor, and if the baptismal process does not address these expressions of racism, we will re-emerge from the baptismal waters with more in common with the Egyptian soldiers than with the Hebrew slaves… an aspect of the miracle of baptism is that the baptismal waters have the power to change us.

TOM ELICH

Editor