Liturgy News

Vol 48 No 2 June 2018

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editor: Touching the Sacred | Elich, Tom | Australian Images | 2 |

| A Journey Through The Mass | Schwantes, Clare | Eucharist / Mass | 3-5 |

| Celebrating Richard Connolly on His Ninetieth Birthday | Taylor, Paul | People | 6 |

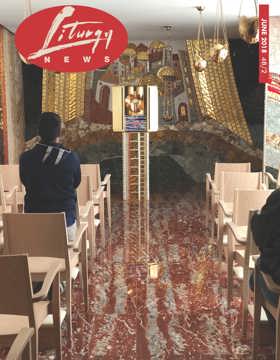

| Our Cover - Our Lady of the Southern Cross, Springfield | - | Architecture and Environment | 7 |

| Five Weeks of John Six | Fitz-Herbert, John and the members of the Liturgy News Board | Eucharist / Mass | 8-11 |

| About Your Subscription | - | Calendar | 12 |

| Thinking About Numbers | - | Sacraments | 12 |

| A Synodal Church | - | Documents on Liturgy | 12 |

| Appointments | - | People | 12 |

| John Ogah - Easter Baptism | - | Baptism | 13 |

| A Baptism and a Wedding | - | Marriage | 13 |

| Composer Honoured | - | People | 14 |

| Remembering Fr O'Flynn | - | People | 14 |

| New Baptistery | - | Architecture and Environment | 14 |

| The Vatican at the Venice Biennale | - | Art | 14 |

| Books: One Love. A Pastoral Guide to the Order of Celebrating Matrimony | Cronin, James | Marriage | 15 |

| Year of Youth | Robinson, James, McGrath, Teresa, and Fenech, Melissa | Children and Youth | 16 |

Editorial

TOUCHING THE SACRED

Elich, Tom

In Australia, it is rare to have a sustained, vigorous and public debate about the nature of the Sacred. Yet this lies at the heart of the issue about Uluru and whether or not to climb it. At the end of last year, after decades of debate, the National Park Board of Management decided that the climb would be closed in October 2019.

Mainstream tourism to the Rock, which had become possible when the first dirt track opened after the Second World War, became frequent during the 1950s. It was promoted as a rock to climb, and success in this adventure created for the tourist a strong sense of pride, achievement and ownership. It was the thing to do.

I first visited Ayers Rock (as it was still commonly known) over twenty-five years ago. Native title had been decided in 1983 and the handback occurred with ceremony and rejoicing in 1985, but in the early 1990s little had changed. On this first visit, most visitors cheerfully attempted the climb and asked no questions.

I returned to Uluru recently and the change was palpable. A cultural centre had been established in 1995 and aboriginal-led tours have been organised. In the shadow of this extraordinary place, both the visitors’ centre and the guided tours opened up the timeless mythology and cultural matrix of the Anangu people. Tjukurpa, they call it: the complex system of meanings which defines and maintains relationships between people, plants, animals, landscape and tradition in this place called Uluru.

It is against this background that the call Please Don’t Climb has become stronger and stronger. One of the traditional owners explained: That’s a really important sacred thing that you are climbing. .. You shouldn’t climb. It’s not the real thing about this place. And maybe that makes you a bit sad. But anyway that’s what we have to say. We are obliged by Tjukurpa to say. And all the tourists will brighten up and say, ‘Oh I see. This is the right way. This is the thing that’s right. This is the proper way: no climbing’.

This is not a matter of who ‘owns’ Uluru or who controls the decision-making process. This is not a matter of religion or of pretending that the stories told by the Anangu will enter the belief system of the nation. For all Australians, it is about understanding the meaning of the Red Centre. It touches something profound about our identity and the mythology of the place where we live: archetypical ideas of the bush, mateship and the Aussie battler; the desert, the wide open spaces and the tyranny of distance.

Uluru has become a national symbol -no, more than that: an icon, a symbol worthy of veneration. It is spiritual impoverishment to reduce Uluru to a logo or marketing image. The thinking of the Anangu people challenges mainstream Australia to revisit its assumptions about this place.

We travel to this extraordinary natural formation at the heart of Australia and marvel at its immensity and its isolation on a vast flat plain. We behold it from close up and far away, at dawn and at dusk. We admire its form and texture and photograph its changing colours. And then, without thinking, we have adopted the mindset of nineteenth-century explorers and we want to conquer it, to climb it and assert our mastery over it. The formal end of the climb forces us to think again.

There are other ways of connecting with this place and appreciating its value. At the handback just over 30 years ago, the Governor General Sir Ninian Stephen spoke of a sense of awe and wonder. When we stand in the presence of the sacred, we do not conquer it, we are conquered by it. Christians understand this, for we stand humbly before the rock of Calvary knowing that the saving death of Christ is mystery and gift. We stand at the rock of the altar and enter into the wondrous sacrament of Eucharist. We cannot control or manipulate these realities by our words or concepts, by our ideas and arguments. We simply behold God’s grace and are transformed.

This may be a difficult lesson for pragmatic and secular Australians, but one does not need to be religious to learn it. Literature and philosophy, art and music will also take us to this place where we know the Sacred.

We can climb walls and bridges in the city, and various peaks and ranges in the country. This is all good and proper, but Don’t climb has given us a new and more profound reason to visit Uluru.

TOM ELICH

Editor