Liturgy News

Vol 48 No 3 September 2018

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editor - Clericalism | Elich, Tom | Eucharist / Mass | 2-3 |

| Liturgy and the Plenary Council | Elich, Tom | Special Celebrations | 4-7 |

| Fire of Recognition | Stapleton, Trish | Indigenous Australians | 8 |

| Infant Conscripts | - | Baptism | 9 |

| Guidelines on Holy Communion | - | Documents on Liturgy | 9 |

| Anglican Dialogue | - | Liturgy - Other Churches/Religions | 9 |

| Agreement on Baptism | - | Baptism | 9 |

| Place for Penance | - | Penance | 9 |

| No Credibility | - | Marriage | 9 |

| Liturgia | - | Liturgy Preparation | 10 |

| The Communion Table | - | Eucharist / Mass | 10 |

| Date Claimer - Symposium | - | Architecture and Environment | 11 |

| Celebrating Guardini | - | People | 11 |

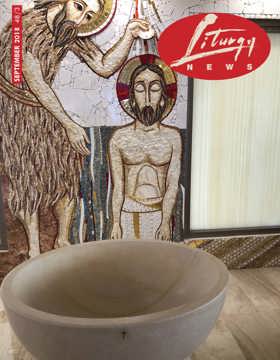

| Our Cover - Our Lady of the Southern Cross, Springfield Lakes, QLD | - | Architecture and Environment | 11 |

| Mystagogy - Rite for the Christian Initiation of Adults | Moore, Michael | Christian Initiation | 12-13 |

| An Interview with Michael Fitzpatrick | Robinson, James | Music | 14 |

| Books: The Rites and Wrongs of Liturgy: Why Good Liturgy Matters by Thomas O'Loughlin | Cronin, James | Liturgy | 15 |

| The RCIA as a Resource for Youth Ministry | Ryan, Chris | Children and Youth | 16 |

Editorial

Clericalism

Elich, Tom

There has been a lot of talk about CLERICALISM. It is a ‘club’ mindset among the clergy, bringing with it a sense of entitlement and privilege. It was often presumed and supported by lay people: people would say, ‘Ask Father: Father will tell us’. It occurred even beyond the Church in society at large: there was a time when Father would get let off his speeding ticket. It is not difficult to see how protecting the ‘club’ could be understood as protecting the reputation of the Church.

The Sunday Mass

I caught myself thinking that the liturgy would be a good counter to clericalism. We celebrate the liturgy as the Body of Christ. It is by our common baptism that we belong to the celebrating Church, and full, conscious and active participation is our right and duty by virtue of our baptism. The very nature of the liturgy calls for all the baptised to be present as doers of the liturgy (SC 14).

Of course the gathered Church is hierarchically structured and the priest ‘presides over the assembly in the person of Christ’ (SC 33). But this service of the people of God does not set him apart from the assembly any more than his ordination overrides the fundamental calling of his baptism.

But then I realised with a sense of horror that our liturgy does not look like this. The priest enters in a procession of honour when all the people are already corralled in their pews, often all facing the front. He is robed in flowing vestments in the colour of the season (and sometimes even clothed in rich gold brocade). He goes to sit in his own big chair. He stands at the front on a podium, gesturing and greeting the people. He reads the Gospel and preaches. He alone stands at the altar holding up the bread and wine and praying aloud. I know, of course, how to explain all this as a ministry of service for the worship of the people. But it doesn’t look like this. It looks like his performance with an audience joining in.

By ordination, the priest exercises a special and essential role in the liturgy, making present the headship of Christ in the Body, to such an extent that the Body of Christ gathered for Eucharist is not complete without him. Without the priest, the Eucharist cannot be celebrated. A marker to designate his particular ministry in the liturgy is necessary. But we have so many markers of difference that we forget the underlying unity of baptism. What would our liturgy look like if we began to rethink these relationships and find a new point of balance?

The Rite of Ordination

Next I looked at the ordination rite to see what the liturgy actually says it is doing when someone is ordained. I have to say I found it embarrassing. Yes, there are a few references to priestly service of the people of God and their pastoral care. But far more common is talk of admission to the Order of Priesthood. The model homily begins by telling the people that this man is now to be advanced to the Order of Priests and asking them to consider the nature of the rank in the Church to which he is about to be raised. The Eucharistic Prayer which follows ordination intercedes for the newly ordained whom you have been pleased to raise to the Order of Priesthood. Notice the terms ‘advanced’ and ‘raised’. When a priest is disciplined, we say he is ‘reduced to the lay state’.

The Prayer of Ordination begins with references to Moses and Aaron who, with their helpers, are set over the people to govern and rule them. Then, when God is asked to grant the ordinand the dignity of the Priesthood, this is defined as being next in rank to the office of Bishop. This does not sound much like a shepherd, smelling of the sheep and accompanying – walking alongside – the flock (to adopt the vocabulary of Pope Francis). This is the relationship which the prayer of ordination might have highlighted. As Archbishop Luc Ravel of Strasbourg wrote in a pastoral letter on 6 September: the sheep belong to Christ and to him alone, but the priest belongs to the sheep.

The actions of the ordination rite might also suggest for people the ordinand’s admission to a ‘clerical club’. Before the Prayer of Ordination, the bishop lays hands on the candidate’s head and all the priests present then do the same. They remain beside the bishop during the prayer. Then, after he is vested, his hands are anointed and he receives the sacred vessels and the bread and wine, the priests all come back to give him a sign of peace.

As with the celebration of the Sunday Mass, all these things can be explained in a reasonable way. But again the liturgy – which should manifest our baptismal unity in Christ – seems to set up a clericalist understanding of priesthood. What would ordination look like if we emphasised the gift of the Holy Spirit for a servant leadership?

Beyond Clericalism

Lumen Gentium, the constitution on the Church from Vatican Council II, first has a chapter on the People of God before pre-senting separate chapters on the hierarchy and laity. It makes clear that our common baptism is a call to share in the ministry of Christ, priest, prophet and king. You are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people, in order that you may proclaim the mighty acts of him who called you out of darkness into his marvellous light (1 Pet 2:9). This refers to the whole people of God.

Lumen Gentium points out that the common priesthood of the faithful and the hierarchical priesthood differ not only in degree but also in essence; yet both are a share in the one priesthood of Christ (LG 10). There is no indication here of a separate or superior clerical class.

In Chile in January 2018, Pope Francis spelled out the betrayal which is clericalism: A failure to realise that the mission belongs to the entire Church, and not to the individual priest or bishop, limits the horizon, and even worse, stifles all the initiatives that the Spirit may be awakening in our midst. Let us be clear about this. The lay persons are not our peons, or our employees. They don’t have to parrot back whatever we say. Clericalism, far from giving impetus to various proposals and contributions, gradually extinguishes the prophetic flame to which the entire Church is called to bear witness. Clericalism forgets that the visibility and the sacramentality of the Church belong to all the people of God, not only to the few chosen and enlightened.

Tom Elich

COMMENT

I asked Paul Chandler O'CARM, spiritual director at Holy Spirit Seminary Banyo, if he would comment on my editorial. He replied, Thank you for asking me. I like what you say, but here are a few rather random comments.

1. Clericalism is a fair target and the examples you give are interesting enough, but it has always seemed to me an ill-defined vice. And it is not unique to priests. There is a ‘clericalism’ of lawyers, for example, and it is not for nothing that managers are called ‘suits’. I think you raise a difficult issue: how the clergy might be purified of a presumptuous clericalism, while still respecting a ritual action where ‘the one’ has the task of representing ‘the many’. Representation itself is a problematic concept in an individualistic culture. The Eucharist contains layers of representation which are not easy to interpret in our time: the priest acts in the person of Christ, and he prays in the name of the congregation.

2. Yes, there is a ‘look at me, I'm special’ aspect to vestments, as you point out. But part of the paradox of dressing up is that there is also an anonymising function to vesture: it represents the office and can hide the person. I've often been struck by how people can fail to recognise you outside church once you're back in your shirt and trousers. So there is a tension there between office and person which is part of the symbolic world in which liturgy functions. It is hard to read when one is not initiated into the world of specific ritual.

3. When I was in Nijmegen, a student there was doing his doctoral thesis on the Ordo Missae. He once gave a very interesting lecture on the first sentence: Populo congregato, sacerdos cumministris ad altare accedit… (‘When the people are gathered, the priest approaches the altar with the ministers…’). He commented that, in nearly all the languages he had checked, cum ministris was mistranslated as ‘with his ministers’ (the clerical mindset!). They are not ministers to the priest but to the community.

Most of his commentary was on the first two words. When the people have assembled, then the priest comes in to serve them. The people come first. This was revolutionary because the people were not mentioned in the Tridentine Missal. There is a new consciousness here of the first real presence of Christ in the community (where two or three are gathered…). Sadly this has still not taken root even after 50 years – newly-ordained priests boast on the internet of how spiritual it is to ‘say Mass’ alone. I have long been amazed that the one-dimensional, dessicated pieties of the post-Tridentine Church have a power over the imagination which the deeper, richer tradition re-opened by Vatican II has not yet managed to establish. Some of the required undoing of the clerical mindset has to come from the laity taking hold of their own baptismal dignity.

4. It is true that the texts of the ordination rite contain the ‘raised to the dignity’ language to which you refer. I always ask ordinands, where are you raised from? The correct answer is, from the floor.

The very last thing you must do before being ordained is lie face-down on the floor. It is a position of maximum vulnerability, as low as you can go, a symbol of surrender to God, and to the prayers of the people (they are singing the Litany of the Saints). If you are raised up, it is on the back of these prayers. Symbol and text have to go together to make sense of the rite.

5. It is often a question of where the emphasis lies. The people cannot begin Mass without the priest; but it is also true that the priest cannot begin Mass without the gifts of the people. In the ordination rite, the new priest receives from the people the sacred vessels with the bread and wine. You pass over this to get to the clergy exchanging the sign of peace, but something you ask for is already there. The ordination liturgy does not proceed until the priest receives from the people what is required for the Eucharist. Perhaps this is not made visible enough, or perhaps we have not been taught to see.

6. Ritual requires initiation. But practically speaking, we have virtually no such initiation. Liturgy is often a spectacle with an audience, not a ritual with participants. Making changes to stress the servant quality of ordained ministry would be desirable but may not go deep enough or make much real difference to people’s perception unless the question of ritual initiation is addressed. How are people in the secularised 21st-century West to have the keys to interpret ritual?

Look for example at what has happened to the funeral liturgy. Instead of the mourners being oriented to the opening-up of a mysterious future with God, it has been re-oriented to the closure of a finished past (the celebration of a person’s life). Partly this has been driven by the funeral industry, partly by secularisation (especially when the mourners are ‘unchurched’), but also because even believing mourners have not been initiated into the patterns and structures of ritual. That is the role of mystagogy, but we struggle to find effective ways and useable opportunities to invite people into the mystagogical process, invite people to enter into the liturgy and the mystery of Christian life.