Liturgy News

Vol 49 No 1 Autumn 2019

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editor: An Easter Imperative | Elich, Tom | Easter and Lent | 2 |

| The Eucharistic Prayer | Craig, Barry | Eucharist / Mass | 3-6 |

| Music at Confirmation | Young, Anthony | Music | 6-7 |

| Liturgical Translation | - | Texts – Liturgical | 8 |

| Australian Academy of Liturgy | - | Art | 8 |

| Australia Day Honours | - | People | 9 |

| Pope on Music | - | Music | 9 |

| Ecclesia Dei | - | History of Liturgy / Vatican II | 9 |

| New Commemoration | - | Saints | 10 |

| Celibacy Discussion | - | History of Liturgy / Vatican II | 10 |

| Liturgy Congregation | - | Catechesis - liturgical | 10 |

| New Chair | - | People | 11 |

| Russell Hardiman | - | In Memoriam | 11 |

| Wendy Beckett | - | In Memoriam | 11 |

| Sistine Chapel Choir | - | Music | 11 |

| Where Your Treasure Is | - | Architecture and Environment | 12 |

| Women's Diaconate | - | Ministries – Liturgical | 12 |

| Confessionals | - | Penance | 12 |

| Ember Days | Briffa, John | Calendar | 13 |

| Leinster, Leonora, Laverton | Dever, Annette | Australian Images | 14 |

| Books: And When Churches Are To Be Built and Fit For Sacred Use | Moran, Julie | Architecture and Environment | 15 |

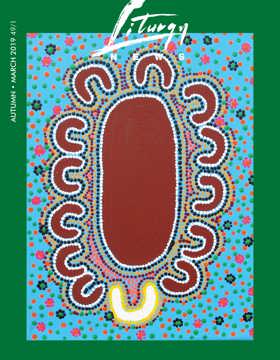

| Our Cover: Last Supper | Timms, Jenny Nakamarra | Australian Artists | 16 |

Editorial

An Easter Imperative

Elich, Tom

The Jews shouted, ‘Not this man, but Barabbas!’ They shouted, ‘If you set him free, you are no friend of Caesar!’ Pilate said to the Jews, ‘Here is your king.’ The Jews said, ‘Take him away; take him away. Crucify him!’

These are the words we hear in John’s Gospel on Good Friday. What we say and think about Judaism in our Easter liturgy, what we sing and pray, read and preach, demands careful discernment and nuance.

I hope we have some of the obvious issues under control. There was an outcry in 2007 when use of the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite was made more generally available. It included a Good Friday Prayer which interceded for the ‘perfidious Jews’ in their blindness, that they would be brought from their darkness into the light of Christ. This prayer was changed. In the 1970s we used to sing brightly of JHWH as the God of our salvation, and the original Jerusalem Bible used God’s holy name JHWH (though our Lectionary replaced it with ‘LORD’). Out of respect we no longer speak the sacred name of God.

So there has been a concerted effort to purge our liturgy of anti-Jewish perspectives. The difficult texts of scripture need careful exegesis when they are preached, and probably judicious editing when the new Lectionary is prepared. We must avoid giving the impression that Jews in general are responsible for the killing of Jesus or are the ‘enemies of Jesus’. Some of those present in Jerusalem at the time agitated against Jesus and certain ones among the scribes and Pharisees. So, should we adjust the Good Friday Gospel to say, The crowd shouted… or Pilate said to the people…?

It is helpful to remember that Jesus himself, as well as Paul and the apostles, were committed Jews. So for example, we see Jesus reading the prophet Isaiah in the synagogue (Lk 4:16-22) and frequently teaching there. Christian liturgy has roots in Jewish prayer forms. The story of the early Church is one of gradual separation from the Jewish faith. Then quite quickly, the proclamation of Christ to the Jewish community was broadened to include the Gentiles. But this brings us to the most delicate issue of all. How do we articulate the relationship between Christianity and Judaism, the new Covenant and the first Covenant?

Sometimes in the New Testament itself and commonly throughout Christian history, the new people of God were understood to replace Israel, the new covenant in Christ taking over the original covenant with God’s people. Hebrews 8:13 is unequivocal In speaking of a ‘new covenant’ God has made the first one obsolete. And what is obsolete and growing old will soon disappear. Combined with the blunt doctrine ‘No salvation outside the Church’, this is clearly unacceptable. It effectively excludes and marginalises Jewish people, treats Jews as a rejected people, and gives rise to misguided missionary endeavours directed at the ‘conversion of the Jews’. Right up until the 20th century, such thinking has led Christians to antisemitism.

But the first covenant stands, since God does not take back the gifts he has bestowed or renege on the choice he has made. The first is not annulled or replaced by the new Covenant in the blood of Christ. This is stated by Paul writing to the Romans (11:29) and affirmed by the Second Vatican Council (Nostra Aetate 4). Instead we are called to recognise that the one God speaks to all through both Old and New Testaments. The commandment to love God and love our neighbour is the common property of both testaments. The two covenants are complementary and mutually affirming. Indeed it may be more accurate to speak of one covenant of salvation in which the one God draws both Jews and Gentiles together.

This is the way we must interpret the Prayer for Jewish People on Good Friday. We ask that they will advance in love of God’s name and in faithfulness to God’s covenant (with them) that the people you first made your own may attain the fullness of redemption. We do not ask that they be saved by faith in Christ and do not make them the object of Catholic missionary activity.

One of the trickiest notions we need to deal with is ‘fulfilment’. A constant refrain in the Gospels is that this or that took place to fulfil the Scriptures. In Christian prayer, we use the psalms within a Christological framework. Jesus, we say, fulfils the prophesy of the coming of a saviour. After reading Isaiah in the synagogue, Jesus exclaims, this text is being fulfilled today even as you listen (Lk 4:21). This does not empty the words of Isaiah of their original meaning, but adds a new dimension to them. None of this should be read as though the New Testament replaces or supersedes the Old. Although Christians believe God is acting to do something new in Christ, the idea of fulfilment suggests that God is always faithful to the promises of old. Do not imagine, says Jesus, that I have come to abolish the laws or the prophets. I have come not to abolish but to fulfil (Mt 5:17).

The challenge we have inherited from our history is well illustrated by the Christian iconography of Ecclesia and Synagoga frequently encountered in the Middle Ages, and usually presented in the form of two young female figures. They were carved, for example, on one of the portals of Strasbourg cathedral in 1230. Ecclesia is crowned and dressed in an imperial robe; she carries a chalice and holds a staff surmounted with a cross and resurrection banner. She looks triumphantly out to the world. Synagoga, on the other hand, looks down in defeat, her staff is broken, she wears no crown and her eyes are veiled. The scroll of the Scriptures slips from her hand.

The Passion narrative in the synoptic Gospels relates that, at the moment Jesus died, the curtain of the Temple was torn in two from top to bottom (Mt 27:51, Mk 15:38, Lk 23:45). This has generally been taken to say that the death and resurrection of Jesus brought an end to Jewish worship in the Temple. Consequently the figures of Ecclesia and Synagoga are sometimes placed on either side of the crucifixion.

It is not a common subject for contemporary art, but a recent example shows an edifying change. To commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Nostra Aetate in 2015, Joshua Koffman was commissioned to make a sculpture for St Joseph’s University in Philadelphia. Here the two women are seated together, both wear crowns and carry the scriptures (a scroll and a book). They are talking together and learning from each other.