Liturgy News

Vol 51 No 3 Spring 2021

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editor: Accompaniment - Je te prends par la main | Elich, Tom | Pastoral Care of the Sick | 2-3 |

| It's not just the Priest! Pastoral Collaboration between Priest and People in Preparing Liturgy | Doran, Anthony | Liturgy Preparation | 4-6 |

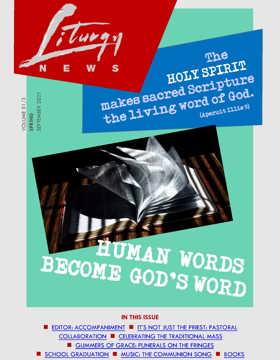

| Our Cover - Aperuit Illis | - | Word | 6 |

| Celebrating the Traditional Mass | Elich, Tom | Eucharist / Mass | 7-8 |

| Traditonis Custodes | - | Eucharist / Mass | 9 |

| Guido Marini | - | People | 10 |

| Year of St Joseph | - | Art | 10 |

| Learn and Discover Courses | - | Catechesis - liturgical | 10 |

| School of Preaching | - | Word | 10 |

| Christmas on Saturday | - | Calendar | 10 |

| Syro-Malabar Church | - | Liturgy - Other Churches/Religions | 10 |

| Anne McMillan | - | In Memoriam | 11 |

| James Leachman | - | In Memoriam | 11 |

| Mass Rocks | - | Architecture and Environment | 11 |

| Glimmers of Grace - Funerals on the Fringes | Ryan, Tom | Funerals | 12-13 |

| School Graduation Ceremonies | - | Children and Youth | 14 |

| The Communion Song: When to Sing and What to Sing. | Mangan, Michael | Music | 15 |

| Books: Preparing Parish Worship | Fitz-Herbert, John | Liturgy Preparation | 16 |

Editorial

ACCOMPANIMENT Je te prends par la main

Elich, Tom

We will soon be facing a difficult and delicate pastoral-liturgical challenge across Australia. It relates to sacraments and the pastoral care of Catholics who are opting for Voluntary Assisted Dying.

VAD legislation has now been passed and is being implemented in Victoria, Western Australia, Tasmania, South Australia and Queensland. New South Wales will not be far behind. Over several decades, lobby groups have been very active in promoting the option of euthanasia in Australia. Needless to say, it is opposed by the Catholic Church (and the Australian Medical Association, among others).

The liturgical question is whether and in what circumstances we may celebrate the sacraments of Penance, Anointing and Viaticum with those who are choosing VAD and whether and how we may celebrate a Catholic funeral for them. The pastoral care process would involve the patient in discussion of alternatives to VAD and options for palliative care. The Church’s minister would advocate the sacredness of human life and trust in God’s providence, with both the person and the family. But how do the sacraments fit in?

The starting point for the Canadian bishops of Alberta and the north-west (Vademecum for Priests and Parishes, 2016) is that euthanasia is never morally justified and that the Church cannot concur or cooperate in

any way with an evil act. For the sacrament of Penance, the penitent should manifest contrition, confession and repentance. To one who has requested death under the law, it should be explained that this is a grave moral evil and, if the person continues on this course of action, absolution cannot be given. Only if the person is open to reconsidering the decision, may the sacrament proceed. Likewise for the Anointing of the Sick, ‘obstinate persistence in manifest serious sin’ precludes the celebration of the sacrament. For a person who has become unconscious, the priest would not presume repentance unless some sign had been given first. Curiously there is no consideration of Viaticum.

For each of the sacraments, the bishops analyse the situation of the patient. Is it a situation of indecision or of a determination to proceed? In the second case, is it a manifest determination or a private determination? In each of these, is it a situation of remote enactment of decision or proximate enactment of decision? The overriding aim is to persuade the person to change their mind.

These Canadian bishops acknowledge that the Church does celebrate funerals for those who died by suicide (there are specific prayers for this in the rite), but they suggest that, if the funeral rite became ‘an occasion to celebrate the decision to die by assisted suicide’, it should be ‘gently but firmly denied’. This is a real danger in Australia given the common aberration of extensive eulogy. ‘Celebrating the life of the deceased’ needs to be carefully monitored and circumscribed to ensure that the person’s heroic embrace of a terminal illness does not glorify or approve of VAD in any way.

In their pastoral letter of 2018, the Canadian bishops on the east coast emphasise the pastoral dimension a little more, recognising that this is a highly complex and intensely

emotional issue. Those opting for VAD, they say, deserve our understanding, respect for their point of view, and a compassionate pastoral response. Pastoral care in difficult situations involves listening closely and accompanying those who are suffering. It is a ministry of healing, guiding, nurturing and reconciling. Our faith in the resurrection affirms that death is not the last word on Christian life. No one should ever be denied the grace of the sacraments whenever there is faith, hope, and an openness to an acceptance of the gift of life. Even when a person’s resolute determination makes the sacraments impossible, say the bishops, we can never abandon them. The Church is called to accompany those considering VAD with dialogue and compassionate prayerful support.

In July 2020, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith released Samaritanus Bonus, a comprehensive letter on the care of persons in the critical and terminal phases of life. As one would expect, the document makes a strong case against euthanasia and assisted suicide: they are always the wrong choice. When a request for euthanasia rises from anguish and despair, although in these cases the guilt of the individual may be reduced, or completely absent, nevertheless the error of judgement into which the conscience falls, perhaps in good faith, does not change the nature of this act of killing, which will always be in itself something to be rejected. The same applies to assisted suicide… Experience confirms that the pleas of gravely ill people who sometimes ask for death are not to be understood as implying a true desire for euthanasia; in fact, it is almost always a case of an anguished plea for help and love. When it comes to the sacraments for those who have requested death, the Congregation affirms the necessity to remain close to the person in a willingness to listen and help, but we find ourselves before a person who, whatever their subjective dispositions may be, has decided upon a gravely immoral act and willingly persists in this decision. This involves a manifest absence of the proper disposition for the reception of the sacraments.

For the Swiss bishops (2019), the starting point is to understand why a person would choose VAD: fear of suffering, the burden of treatments, loneliness, a feeling of being useless or a burden on others, loss of dignity… The desire for death most often expresses a vulnerability on the part of the sick person. The best way to set the person on a new course is by love and solidarity. Ecclesial accompaniment, undertaken with delicacy and respect under the tender and merciful care of God, engages with the desire for death in hope of transforming it into a desire for life. While making it clear that no sincere intention or circumstance can change or justify a bad act, the pastoral carer should accompany the person ‘as far as possible’. The pastor should physically leave the room at the actual moment of the act of euthanasia, not to signify abandonment, but to make it clear to all that there is no cooperation or acceptance of the act. After it is done, however, the minister may decide to return to the patient’s side for the period (an average of 25 minutes) before death occurs. A decision about the sacraments requires careful discernment, not only of the circumstances, but also of the person’s interior attitude. If the decision is reached that the sacraments are not appropriate, it should never be seen as a punishment, nor as the rigid application of a rule, but a stance in favour of life which in turn affirms God’s love for each of us. It is never the end of the relationship of accompaniment. Moreover, the ministry of prayerful empathy extends to the sick person’s family and friends.

The Belgian bishops (Je te prends par la main, 2019) offer a beautiful meditation on death as a profound transition in human existence and celebrate the possibilities of being present through good palliative care. Their letter is meant to encourage pastoral ministers never to abandon a person, no matter what happens. This is an art. They rightly point out that the sacraments of Penance and Anointing, sacraments of healing, are not meant for the time of death but for a much earlier stage in a terminal illness. Most important is to hear the real question behind the request for death. When and why does suffering become intolerable? What happens between raising the issue of euthanasia, requesting it, and passing on to the act? Here the ministry of pastoral accompaniment enters, without judgement and with a profound respect, working collaboratively with family and friends, doctors and carers.

When a person moves through to the act itself – a decision in conscience which cannot be supported by the Church’s minister – the pastor nevertheless remains by the person’s side. Powerless and overwhelmed, the pastor is called to suffer, as indeed do the family and friends. Being with a dying person is very intense, difficult, and very beautiful. Fear, anger, helplessness and sadness are mixed with affection, hope, gratitude, acceptance and faith. We suffer with Christ; we rise with Christ. The witness of the pastor is that nothing can come between us and the love of God, made visible in Christ (Rom 8:38-39).

The issues raised by these episcopal statements are important and difficult.

We can see a gradated approach as we read through them. I can understand the clarity of the Canadian arguments, but I am much more challenged by the ambiguity of the Belgian positions. Certainly we have to be clear where we stand on VAD, but pastorally and liturgically this may not be the most important thing to focus on at the bedside. With all of the positive spin put on assisted dying and given the large number of Australians who support it as something caring and good, it is not surprising that some Catholics will in conscience decide that it is a legitimate option for them at the end. The bishop of Honolulu recently wrote that when someone says, ‘I am at peace with my decision’, it may simply indicate an inflexibility to reconsider. I do not think this is good enough. Whether we agree with it or not, we need to respect a person’s final decision in conscience. For a person in good conscience who requests it, communion as Viaticum is an assurance that Christ is always near to us, imperfect though we be, and that God’s love is sheer unmerited gift.

Christ really did die on Good Friday, and hope was extinguished. Between Good Friday and Easter, a long silence reigns. Then, in the obscurity of Easter night, at the heart of the most profound suffering, the love of God is reborn, stronger than death, and a passage is opened up to fullness of life. (Based on the final pages of Je te prends par la main.)