Liturgy News

Vol 51 No 4 Summer 2021

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editor: To boldy go... | Elich, Tom | Documents on Liturgy | 2-3 |

| Lift Up Your Hearts: Completing the Initiation of Children | Craig, Barry | Sacramental Preparation | 3-5 |

| Liturgical Practice in a Humble, Healing and Merciful Church | Condon SGS, Clare | Plenary Council 2021-2022 | 5-6 |

| A Liturgist Attends the Plenary Council | Orr, David | Plenary Council 2021-2022 | 7 |

| Postquam Summus Pontifex | - | Texts – Liturgical | 8 |

| New Missal in French | - | Texts – Liturgical | 8 |

| Consolation and Hope | - | Pastoral Care of the Sick | 9 |

| A Gender Star? | - | Texts – Liturgical | 9 |

| Cardinal Cupich | - | People | 9 |

| art.catholic.org.au | - | Art | 9 |

| Pope Speaks to Jesuits | - | Texts – Liturgical | 10 |

| Patricia Logan | - | In Memoriam | 10 |

| Eileen Brown SGS | - | In Memoriam | 10 |

| Medina Estévez | - | In Memoriam | 10 |

| New Papal MC | - | People | 10 |

| Honouring Sunday | - | Sunday | 10 |

| Australian Lectionary | - | Texts – Liturgical | 11 |

| Matisse: Life and Spirit | - | Art | 11 |

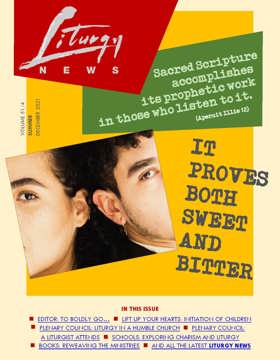

| Our Cover - Aperuit Illis | - | Documents on Liturgy | 11 |

| Charism and Liturgy: The Paths do Connect | Sultmann, Bill | Schools | 12 |

| Charism of the Good Samaritan | O’Rourke, Ursula | Schools | 13 |

| Books: Reweaving the Ministries: The Emmaus Paradigm by Gilbert Ostdiek | Cronin, James | Ministries – Liturgical | 14-15 |

Editorial

To Boldly Go...

Elich, Tom

The timid are often tempted to turn back to what is familiar, to take refuge in the securities of the past. Sixty years ago, we moved the altar forward and the priest faced the people as they celebrated Eucharist. Some were alarmed that this placed too much focus on the priest and his actions. So a movement grew advocating that churches revert to an arrangement where priest and people all faced towards the East together. The problem however was not that we had gone too far; it was that we had not gone far enough. We need to take the next step and place the altar and the priest in the midst of the assembly. Grouped around the altar rather than sitting in rows ‘facing the front’, people can begin to understand that all share in the liturgical offering made at the altar. This is the ‘full, conscious, active participation’ that the Vatican Council set out as the liturgical norm. The Council calls us to boldly go where no one has gone before, so to speak, in finding new ways to implement its vision.

Such a bold, forward-looking perspective is characteristic of Pope Francis’ leadership of the Church and is enshrined in several recent Roman documents. The pope has encouraged us to find new pastoral ways of including those who are marginalised in the Church’s liturgy, from the divorced and remarried, to those in same-sex relationships, to peoples living in the Amazon.

Another challenge to be bold comes with Pope Francis’ provisions overturning Benedict XVI’s normalisation of the old liturgical forms from the 1950s which predate the reform of the Vatican Council. Those who have embraced the liturgical use of the Council of Trent appear to have taken fright at a liturgy which is more extrovert. They fear that, with the assembly singing and responding, with everyone exchanging the peace and receiving communion in the hand, there is a loss of reverence and a sense of the sacred. They seek a return to the more introverted silence of the Tridentine rite, which is deemed to be more meditative and holy. They insist they do not want to be divisive and they maintain that they accept the reforms of Vatican II. But the Tridentine rite does not express the theology of the Church as the Vatican Council presents it. The Church is the whole community of the baptised and the liturgy is the communal action of the entire people of God. The active participation of all is both demanded by the nature of the liturgy itself and is also the right and duty of the baptised.

The thinking underlying the liturgical reform is challenging and may be difficult for some. However, we need to respond not by retreating into familiar and comfortable forms, but rather by moving forward boldly. We need to ensure that the reformed liturgy manifests more clearly the sense of the sacred, making space for the silence in which we receive God’s revelation. We need to make our liturgical symbols and actions so beautiful, so authentic, that they do speak to us of the saving action of Christ. If we stepped forward more boldly, there might be less reason for others to retreat.

The use of the vernacular in liturgy is another evocative example. Since the use of the mother tongue, whether in the Mass, the administration of the sacraments, or other parts of the liturgy, frequently may be of great advantage to the people, the limits of its use may be extended, declared the Vatican Council (SC 36.2). The vernacular took hold very quickly, more quickly than anyone had imagined. Soon the whole liturgy was spoken aloud and everyone could understand what they were listening to and praying. We were delighted that the words of Scripture and liturgical prayer came spontaneously to our lips.

Once again, however, gradually a reaction began to develop. How could we speak to God in the normal language of everyday life? Should we not have something more formal, more strange, for our liturgical language? Some remembered prayers in the old hand missals which read like this: Quickened by thy holy gift, we give thee thanks, O Lord, and we beseech thy mercy, that thou wouldst make us worthy to partake of it (Postcommunion, 18th Sunday after Pentecost). The reaction of retreat culminated in 2001 with the Holy See’s instruction Liturgiam Authenticam. It deliberately set aside contemporary usage in favour of what it called ‘sacral language’. Style manuals for good English were explicitly rejected in favour of a word-for-word rendering of the normative Latin. For over a decade now we have been praying the Mass with convoluted sentences, exclusive language, strange words like oblation and addressing God as your majesty.

In 2017, Pope Francis turned back this retreat, changed the Code of Canon Law, and urged bishops conferences to take charge once again of producing and approving authentic vernacular translations. The boldness of Magnum Principium took bishops by surprise. The English-speaking bishops were paralysed and sought clarification. The post-conciliar vision of the vernacular was indeed being reinstated: [In translating biblical and liturgical texts] it is necessary to communicate to a given people using its own language all that the Church intended to communicate to other people through the Latin language.

Now a new document (Postquam Summus Pontifex) published on 22 October 2021 spells it out in great detail. What is a faithful translation? The adverb ‘faithfully’ implies a threefold fidelity: firstly to the original text, secondly to the particular language into which it is translated and finally to the comprehension of the text by the addressees who are introduced to the vocabulary of biblical revelation and liturgical tradition (PSP 20). The third element here recognises that the liturgy is a means of oral communication and so attention must be given to the fact that the texts are intended for proclamation, for listening to, and for choral recitation and singing.

So after two decades or more of looking backwards, we are again encouraged to look forward boldly. After a 25-year struggle, we have the green light to move ahead with a new Lectionary translation. The possibility of revising the prayers of the Missal, which the Australian bishops have been considering, is now a real possibility. The 1998 Revised Sacramentary, which at the time was roundly rejected by the Holy See, will be resurrected and will help us to boldly go… into a new era.