Liturgy News

Vol 54 No 3 September 2024

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editor: A Tale of Two Churches | Elich, Tom | Architecture and Environment | 2-3 |

| Are Our Liturgies for Everybody? A Pastoral Reflection | Ryan, Tricia | Inclusion | 3-5 |

| Liturgy in Schools | McGuire, Judy; Harrington, Elizabeth; Crooks, Gerry and Schwantes, Clare | Schools | 6-7 |

| Music and Infant Baptism | Brosig, Simone | Music | 7-8 |

| Fire and Water: Death and Resurrection | Elich, Tom | Australian Images | 9 |

| What do you want me to do for you? Pastoral Care of the Sick and Dying | Norris, Judy and Fitz-Herbert, John | Pastoral Care of the Sick | 10-12 |

| Bishop Kevin Manning | - | In Memoriam | 12 |

| Dr Nathan Mitchell | - | In Memoriam | 12 |

| Bishop Timothy Dudley-Smith | - | In Memoriam | 12 |

| Walsingham Feast | - | Calendar | 13 |

| Four Priorities | - | Conferences and Special Events | 13 |

| Jubilee Year - Pilgrims of Hope | - | Calendar | 13 |

| Palm Island - 100 Years | - | Special Celebrations | 13 |

| Bread and Wine | - | Eucharist / Mass | 13 |

| AAL Conference | - | Conferences and Special Events | 14 |

| Synod - Reconciliation | - | Conferences and Special Events | 14 |

| Eileen O'Connor | - | Saints | 14 |

| Eucharistic Congress 2028 | - | Conferences and Special Events | 14 |

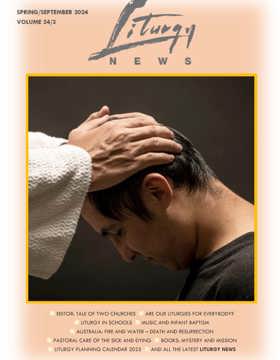

| Our Cover - Hands | - | Sacraments | 14 |

| Books: Clare Schwantes (editor) - Mystery and Mission: The Art of Celebration | Cronin, James | Liturgy | 15 |

Editorial

Editor: A Tale of Two Churches

Elich, Tom

The story, the history, of the place where we worship shapes our worship experience in the building. A church built by an impoverished post-war migrant community brings a particular resonance to the liturgy celebrated there, even decades later. A 19th century parish church might suggest that we deal with our colonial past when we stand at the altar. A church originally in a working-class neighbour-hood might now be located in a very well-off inner-city suburb. Perhaps a country church was built in a farming or mining area. When we gather, we are conscious of those who have gone before us, those who built the church, and on whose faith we rely even today.

When I was on holidays recently in Mexico and Colombia, I was particularly struck by how strongly history creates a context for worship.

he Cathedral of the Assumption in Mexico City was a particularly striking example. It is a magnificent edifice, a world heritage site, built over 250 years spanning the 16th to the early 19th centuries. It is the oldest and largest cathedral in Latin America. Its style shifts from Renaissance to Baroque to Neo-Classical. It is modelled on the Spanish cathedrals of Jaén and Valladolid and, as is common in Spain, has monumental choir stalls built well down into the main nave. It has two impressive 18th century organs, a peal of 23 bells, and dozens of chapels, each adorned with a magnificent altarpiece carved and gilded. A connected baroque building houses the tabernacle and baptismal font.

This cathedral in the New World offers a powerful testimony to the continuity of faith and worship with the Church of Europe. But there is a darker side to the history which also impinges on today’s liturgical celebrations in this place. The Spanish conquest of the 16th century was violent and bloody. Thousands of Aztec citizens, assembled for a religious festival, were massacred here and their sacred temples were sacked and looted. Indeed the mighty cathedral itself was built over the destroyed Aztec temple complex (Templo Mayor) and the very stones of the Aztec temples were used to construct the cathedral. Only in the 20th century have the Aztec ruins beside the cathedral been rediscovered and excavated. This extraordinary juxtaposition, historical and geographical, forces today’s worshippers to remember and humbly acknowledge the ruins which became the foundations.

y second tale comes from Columbia, a town called Zipaquirá near the capital Bogota. For centuries before the arrival of the Spanish, this was the site of a salt mine. Today the veritable mountain of salt has multiple tunnels and huge caverns over four levels from which the salt has been excavated. This mining has always been dangerous and arduous work. For centuries extracted by hand, the close atmosphere and salt dust affected the lungs and caused dehydration. The life of the miner was both gruelling and short. Even since pre-Christian times, small shrines were erected where the miners sought divine help and protection. Christian shrines proliferated in the 1930s and, in 1950, grew into a worship space, the first ‘cathedral’. Following structural failures due to blasting, it was closed in 1992, but a new larger ‘cathedral’ was begun below the old one.

Today, this extraordinary salt cathedral, located 200 metres below ground, can seat over 900 people. In its walls can be seen the marks of the miners’ pick. There are three naves 20 metres high representing birth, life and death. The first contains the baptismal font and a huge nativity sculpture, the second is the main worship space dominated by a 16-metre cross carved into the wall, the third houses a monumental sculpture of Christ’s deposition from the cross. The most impressive sculpture occurs along the long tunnel of descent where huge modern crosses carved into the rock salt walls represent Christ’s Way of the Cross. Each station gives glimpses into the voluminous caverns along the way.

For me, taking part in Sunday Mass in this place was a most moving experience because I could not but be conscious of the suffering, pain and labour of the thousands of miners who forged this space through the centuries. When we speak of the liturgy and social justice, the theological foundation is the reality that the liturgy is the work of the Church, the whole Church of God, and not just the gathered assembly. Thus standing at the altar, we are one with Christian communities in every part of the world – those in war-torn areas and places of persecution, famine and extreme poverty. They are with us as part of the Body of Christ. How can we celebrate the sacrament of unity unless we are engaged with them all?

In the Cathedral of Salt, there is a palpable sense of solidarity with those who labour and are burdened. One becomes acutely aware that the followers of Christ are called to take up their cross and follow him to Calvary, that suffering with Christ is the path to transformation, transfiguration, resurrection. It is precisely Christ’s Paschal Mystery that we celebrate each time we gather for Eucharist. These spaces for worship provide a most challenging and evocative context as we eat the bread broken for the life of the world and drink the blood poured out for the salvation of the world.

Pope Francis spelled it out in 2022: our amazement, our astonishment at liturgy is that the paschal mystery of Jesus’ suffering, death and resurrection is rendered present in the concreteness of sacramental signs: in bread, wine, oil, water, fragrances, fire, ashes, rock, fabrics, colours, body, words, sounds, silences, gestures, space, movement, action, order, time, light. (Desiderio desideravi 24, 42). He states baldly: The content of the bread broken is the cross of Jesus (DD 7).

Never has this been clearer to me than in the tale of these two churches I encountered recently. I believe the background story of our own parish churches is a dimension worth exploring as well.

Tom Elich